If this bout brought victory and global fame for Ali, some six months earlier —in April of the same year— a Baguio-born civil engineer of humble beginnings had already marked a personal career victory that in itself was no mean feat: his appointment, at age 45, as president and chair of Pilipinas Shell Petroleum Corp., and country chair of the Shell group of companies—the first Filipino to hold both posts.

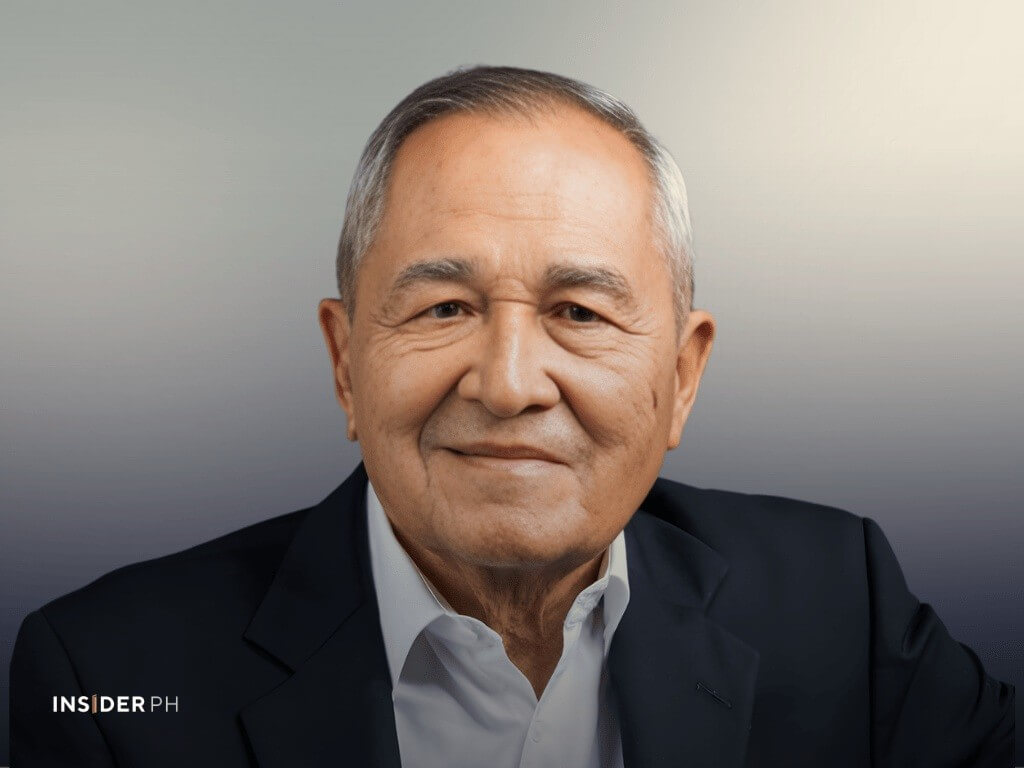

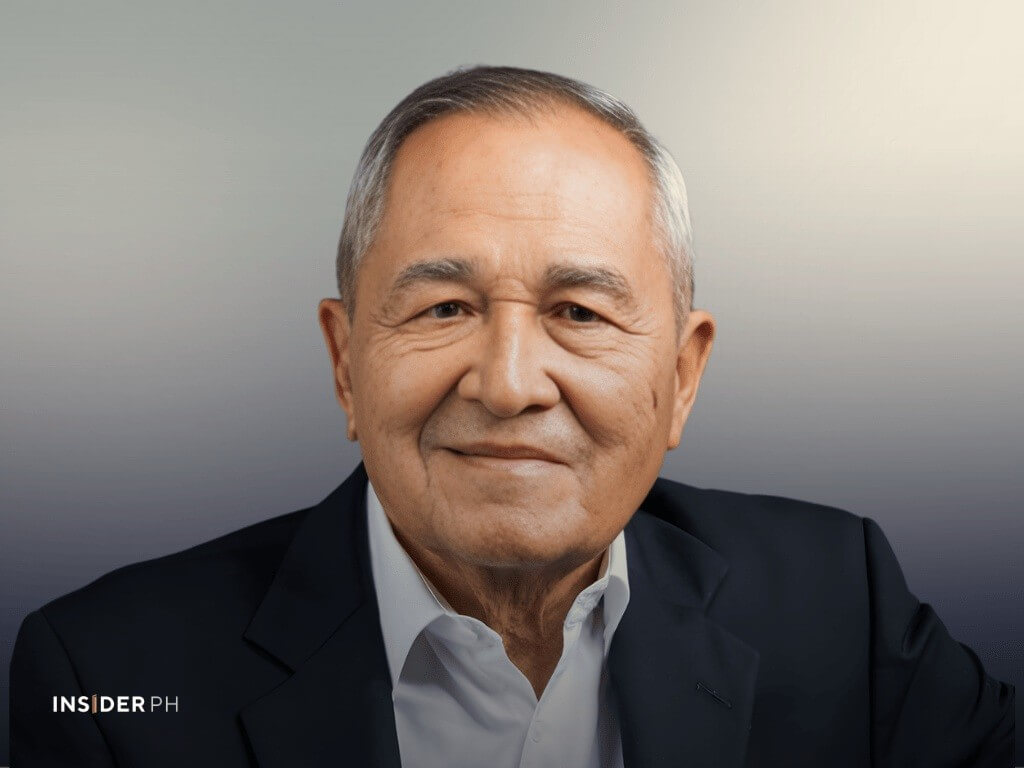

That man was Cesar A. Buenaventura—fondly known as CAB—who died on Dec. 10, 2025, at age 96. From overcoming illness as a child and surviving the ravages of World War II, to studying abroad on a Fulbright scholarship and reaching the pinnacle of the corporate ladder as the head of a multinational petroleum company, Buenaventura’s life was the stuff of legend.

Family roots

Buenaventura was born on Dec. 18, 1929, in Baguio City, some 46 kilometers from Aringay, La Union—the hometown of his mother, Consuela Baltazar. Hailing from a political clan, she was “a mestiza of Filipino, Spanish, and French ancestry.”

Meanwhile, his father, Antonio Buenaventura —a civil servant who worked his way through high school —was from Imus, Cavite, and came from a family of fishermen, farmers, market vendors, and the like. Antonio’s itinerant work in government took him from Cavite to Batanes, where he served as provincial treasurer, then to Zambales, Surigao, and finally Baguio.

The union of Antonio and Consuelo in December 1928 would later bring them five children. Aside from Cesar, there was Elisa, a social worker who served as treasurer of the Asian Social Institute; Jose Fernando, or Chito, a lawyer and senior partner at the Romulo Buenaventura Law Firm; and Rafael, or Paeng, who would later serve as Central Bank governor and passed away in 2006. Another daughter died in infancy.

Contracting pneumonia at 18 months old, Cesar spent four months convalescing at the Baguio General Hospital, owing his recovery and ability to walk to Dr. Teodro Arvisu, a close friend of his father.

“It was a sleepy town most of the year,” Cesar recalled of the Baguio of his youth in “I Have a Story to Tell,” Volume 1 of his autobiography. “It came alive due to the influx of government officials.”

Growing up in La Union

If not for Consuelo’s desire to stay close to her elderly parents, Antonio would have wanted to remain in Baguio. Instead, in 1934, the Buenaventuras moved to San Fernando, La Union—“a progressive province,” Cesar remembered, as he walked to school and church—where Antonio served as provincial treasurer.

While Antonio’s monthly government salary of P500 was enough for the Buenaventuras to live a relatively middle-class lifestyle—a two-story rented house with a garage and a car—it was Consuelo’s frugality and business sense that enabled her to acquire fish ponds and rice fields, investments that proved useful in surviving the war.

Wartime displacement

In 1941, upon the arrival of the Japanese, the family evacuated to Manila, staying first in a small house in Sta. Ana and later in Singalong, where they had the Ramon Magsaysay family—using the assumed name Llamas—as neighbors.

“Manila was relatively quiet,” Cesar recalled of that early, dark, and uncertain period. “There was no activity. The exception was the bombing of Corregidor. If you went to the boulevard, you could see the planes and the ships across the bay. You could hear the distant booming sounds.”

Becoming a La Sallian

At this juncture, at age 13, Cesar entered La Salle, studying there until the family had to move back to Baguio in 1944—forcing him to miss recognition day. Disappointing as it was, Cesar nevertheless reflected:

“I realize that a lot of those guys that I met in La Salle and UP became my network later. I never could have had these connections had I stayed in La Union. My life changed because of the people I met and the things that happened during the war.”

When La Salle organized an orchestra, Cesar played the violin alongside Doy Laurel—an instrument Cesar would try to master outside of school.

After Liberation

With Manila in ruins following the Liberation, Cesar left Baguio and, with one suitcase, entered the University of the Philippines Manila’s College of Engineering along with 150 other freshmen—a mix of public school graduates and those from elite Manila schools—staying with his father’s relatives in Singalong.

A member of the Beta Epsilon Fraternity and a cadet major of the ROTC, Cesar was also active in student government, where he was elected vice president of the University Junior Student Council.

In 1950, he earned his civil engineering degree, by which time the university had moved from Padre Faura to Diliman, with only 35 graduates out of the original 150. Taking the board exams, he placed 12th.

Cesar’s first job was at Sta. Clara Construction, serving as a trainee engineer assigned to the UP Arts and Sciences Building project.

A subsequent introduction to David M. Consunji, who was then starting his own construction company, led not only to employment as David’s assistant, but to a lifelong friendship, with Cesar later serving as vice chair of DMCI Holdings until his passing.

Still, Cesar’s ultimate ambition was to save enough money to pursue further education in the United States, later entering Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, under a Fulbright scholarship. Taking the cargo freighter SS Hoegh Silver Spray from Manila to San Francisco, the journey would take 21 long days, followed by a train ride.

Life at Lehigh University

Although he had originally hoped to attend Cornell but could not secure a scholarship, Cesar earned his master’s degree in just a year and a half and became close friends with two Dutchmen, his roommates in a rented attic apartment.

“The dining room was small. We shared one bathroom and a living room. They gave us double-decker bunk beds. It was very frugal,” Cesar recalled.

From hard-earned savings and stipends sent from home, he was able to buy a car—a Pontiac, a personal trophy of sorts—which he later shipped to the Philippines, much to the delight of his brothers Chito and Paeng.

Following a brief stint as a supervising engineer on the Walt Whitman suspension bridge connecting Philadelphia and New Jersey—“exposing me to the multifaceted U.S. construction industry and the powerful U.S. labor unions”—Cesar returned home, setting sail for Manila and arriving in September 1955.

Soon after his return, Cesar sought out his friend and mentor David Consunji, who was then involved in the construction of the UP Chapel designed by a young architect—the future National Artist Leandro Locsin. Serving as Consunji’s assistant on the project, a pioneering endeavor that tested the capabilities and limits of poured concrete, Cesar was assured of continued employment, along with an offer to serve as an assistant professor at UP.

But around this time, a wave of regionalization was sweeping multinational firms, with the aim of appointing local executives to run their operations. The Shell Company of the Philippines, a British-Dutch concern established in 1913, was no exception.

A leap of faith: joining Shell

When an opportunity arose for Cesar to join the firm, he sought Consunji’s blessing and accepted the role of staff operations executive trainee on probation for one year.

This leap of faith—a world far removed from bridges and suspension cables or concrete structures and their PSI measurements—would prove to be the catalyst that enabled him to one day helm one of the country’s so-called “Big Three” oil firms.

Taking on various postings at Shell—from Cebu in 1956 to Poro Point and Iloilo in 1957 and 1959, respectively, always with positive recommendations from his immediate superiors—it was the successful turnaround and reorganization of the Pandacan Oil Depot under Buenaventura’s watch that caught the attention of upper management, all expatriates.

The task was not without difficulty: employees were resistant to change, clashes erupted with the labor union, and a violent strike eventually broke out—it was a virtual no man’s land.

“We held firm during that forty-day period,” Cesar recalled. “We lost 30 percent of the business in Metro Manila. There was also violence. Shots were fired at the installation office. At one point we even had to evacuate.”

Despite sharp criticism from naysayers, he succeeded in having the strike declared illegal—“by some unorthodox measures.” All union officers were dismissed, and workers eventually returned to work.

A year later, Cesar would be assigned to London, with a cross-posting to Holland. Thereafter, with a refinery in development and in operation, he quickly rose through the ranks—operations manager, executive vice president, acting president, and finally president in 1975.

“For a person of my generation, the culture in Shell was very refreshing; you did not feel discriminated against,” Cesar said. “The fact is, I experienced a cross-pollination of ideas and methods with the expats who worked with me and to whom I reported.”

In December 1989, over three decades after making the life-changing decision to join the petroleum industry, Cesar Buenaventura retired from active management at Pilipinas Shell. He remained on as non-executive chair for two years and later as a director, capping a corporate career defined by hard work, steady leadership, and a willingness to take on difficult challenges—often swimming against the tide and venturing into uncharted waters.

Beyond Shell

Outside of Shell, Cesar served as director of Ayala Corp., Benguet Corp., Philippine National Bank, First Philippine Holdings, and DMCI Holdings, among others.

He was a member of the Monetary Board and the Makati Business Club, served on the board of regents of the University of the Philippines and the board of trustees of the Asian Institute of Management, and was president of the Benigno S. Aquino Foundation. He also served as chair of the Philippine Business for Social Progress (PBSP).

An avid golfer, Cesar was married twice. His first wife was Lucia Nanette née del Prado, who succumbed to cancer in 1989 after 32 years of marriage; they had five children. He later married Bambina née de Leon, who was also widowed.

In 1991, Cesar A. Buenaventura was made an Honorary Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Features Reporter