But a closer look shows that corruption is only one aspect of the problem. Sometimes, the issue is something more mundane but, potentially, more damaging to public trust: bad data.

Ghosts in the machine

According to former Public Works Secretary Manuel Bonoan, for example, only two undertakings in Bulacan qualify as genuine “ghost projects” out of the 15 that have been tagged as “missing.”

Apparently, the rest are very real. Flood control structures and dikes that were built, but their coordinates were never updated in the agency’s project monitoring systems.

As Undersecretary Maria Catalina Cabral explained during a livestreamed Senate hearing, the now-controversial department uses two key systems: the Multi-Year Programming and Scheduling (MYPS) tool, which records planned locations and timelines, and the Project Contract Management Application (PCMA), which holds contract implementation details.

Unless implementing offices manually update the coordinates after relocation or adjustments — often caused by right-of-way issues or technical considerations like changes in river flow — the data in MYPS and PCMA will not match reality.

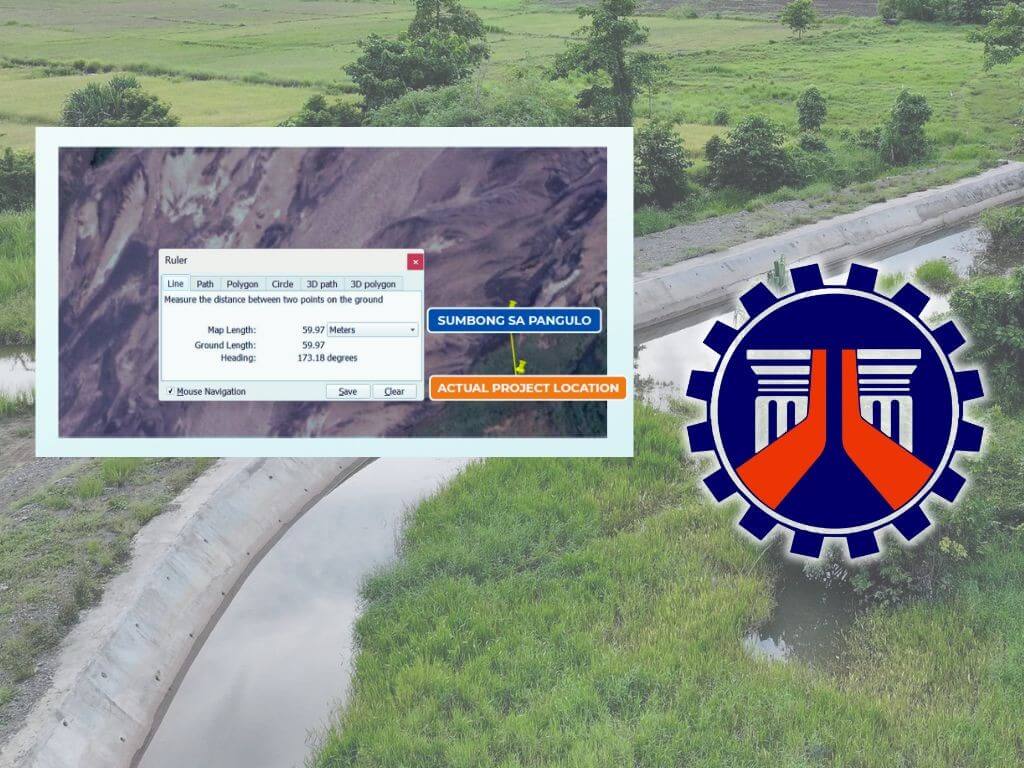

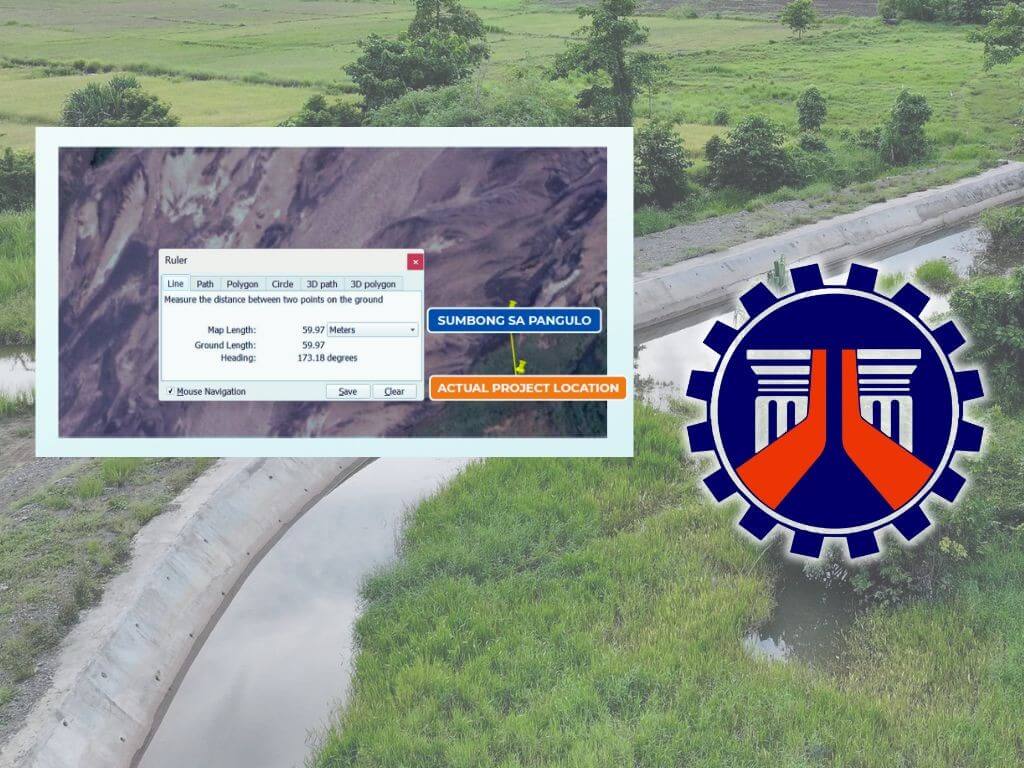

Because of this, platforms like Sumbong sa Pangulo, which pull preliminary or outdated coordinates solely from MYPS and PCMA, end up flagging projects in the wrong locations.

Garbage in, garbage out

This is an important consideration because there is a simple rule in information systems called “garbage in, garbage out.” If the input data is flawed, the output — whether in the form of maps, dashboards, or policy recommendations — will also be flawed.

This is what’s happened with some of DPWH’s project data.

While there are undoubtedly eye-watering levels of corruption within the department (and with external stakeholders like contractors, lawmakers, and local government officials) the public may be getting angry at the wrong projects, in the wrong places.

Worse, lawmakers and even the President himself may be reacting to inaccurate information.

Examples included in DPWH’s own internal presentation that were shared with InsiderPH illustrate the problem. In Oriental Mindoro, flood mitigation structures along the Panggalaan River were correctly built, but preliminary MYPS-PCMA showed them hundreds of meters away. To an ordinary citizen checking Sumbong sa Pangulo, it looked like money was spent on thin air.

Why this matters

At best, inconsistent data wastes time and resources. Senators haul DPWH officials to hearings, staffers trek to field sites looking for non-existent structures, and news headlines scream about “ghost projects” that may or may not exist.

At worst, inaccurate data creates openings for exploitation. Political operators can weaponize discrepancies to smear opponents, undermine institutions, or shake public confidence in government.

In a country where corruption scandals routinely erode trust in public agencies, DPWH cannot afford to be cavalier about data accuracy. When floodwaters rise or roads collapse, Filipinos expect answers — not excuses about mismatched coordinates.

What DPWH should do

First, the department must automate location updates. Relying on manual inputs by field engineers invites errors and delays. With today’s technology, geotagged photos and GPS data can be automatically synced to central systems.

Second, it must establish a data audit trail. Policymakers and the public must be able to trace how project data changes over time — from planning to implementation.

Third, the department must strengthen public communication. When errors are discovered, the agency should proactively explain them. A citizen seeing a misplaced project marker online should not be left to assume corruption.

Finally, it must treat data as infrastructure. Just as roads and bridges need maintenance, so do databases and information systems. Budget allocations for IT upgrades, staff training, and cybersecurity should not be afterthoughts.

The bigger picture

On top of the bigger corruption issue, the ghost project controversy is also a cautionary tale for all government agencies that rely on digital dashboards and open data portals. Transparency is meaningless if the information provided is inaccurate.

Policymakers, from senators to Malacañang, need reliable inputs to make sound decisions. Inaccurate coordinates may seem like a small technical glitch, but in practice, they can distort budget allocations, misdirect investigations, and fuel public outrage based on false premises.

When the public loses confidence in government data, every infrastructure project becomes suspect. Even legitimate, well-executed works risk being dismissed as scams.

Bottom line

The Senate hearings may yet expose genuine anomalies, and DPWH must answer for them. But it has also become clear that governance integrity depends heavily on data integrity.

DPWH’s mandate is not just to build roads and flood controls. It must also ensure that the information it provides — to Congress, to the President, and to the people — is accurate, timely, and reliable.

Anything less, and the ghosts haunting its spreadsheets will keep coming back.

Senior Reporter